German expressionism evokes blue horses, lavish nudes in natural settings, portraits revealing deep emotions- in short, a liberation from the corsets of academic art. During the period 1900-1930, political turmoil, rumbles of war, crushed dreams of a lower class abandoned by the industrial revolution, threats from infectious diseases, contributed to a state of angst reverberating through the art world. It is also a time of inner self-discovery spearheaded by Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis and Karl Jung, his younger disciple. The Anxious Eye: German Expressionism and Its Legacy at the National Gallery of Art assembles more than one hundred works created from 1908 to 1921, selected from its permanent collection. The display of mainly prints reflects a renewed interest for the cheaper and faster process involved in their production. It also features drawings, two sculptures and illustrated books. The small size of the works allows for a rich show organized by themes, set in four galleries of the West building.

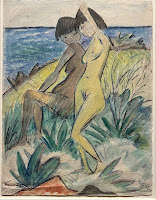

Moving on, Nature and Spirituality might feature soothing landscapes, maybe even a blue sky? Two Pietàs (Max Oppenheimer and Georg Ehrlich), Christ Bearing the Cross (1916) and The Fall of Man (1919), from Lovis Corinth, and other religious themed prints feature more harrowing scenes of suffering, suggesting a redeeming spiritual value to humanity's misery. Close by the mountains from Kirchner or the fishing steamer from Emil Nolde appear irrelevant in the midst of a tormented world while the sunrise from Heckel is filled with bad omens. Communion with nature implies nudity, and nudes are plentiful in two of the galleries. Set in primal surroundings, forests, beaches, the models are caught in playful or more contemplative activities. Kirchner is well represented so are Mueller, Pechstein and Heckel. Angular, sharp lines, sickly yellowish colors, the portraits-caricatures reflect the technique of the German expressionists, transforming the Arcadian settings into depressing sights. The erotic nude from the Austrian Egon Schiele stands out with its generous shapes and decaying flesh. Against this somber background, a carefree and permissive atmosphere floated in some circles, evoked in two lithographs about dance and cabarets. The scantily clad dancer in Tänzerin (1913) from Nolde refers to black performers favored by a white bourgeois audience looking for a steamy entertainment.

Colors and size of the seventeen works in the last gallery contrast with the mostly black and white display so far. A dozen artists, from various backgrounds and continents have been selected and their works cover about seventy years, from the 1950's until today. They have little in common and never met, but are assembled under the theme: German Expressionism Reimagined. If the works from Georg Baselitz and A. R. Penk both Germans relate to neo-expressionism, a loosely defined international movement born in the 1980s, it is odd to find David Driskell's self-portrait inspired by "African art but as seen through the lens of ancestral legacy rather than European colonialism" (wall text). On the American side, Leonard Baskin with The Hydrogen Man (1954) belongs to the list of neo-expressionist artists. His self-portrait is hung between Shikō Munakata, a printmaker inspired by Van Gogh, Buddhism and Japanese folk art, and a woodcut from Kerry James Marshall. One can question the inclusion of Sam Francis considered an abstract expressionist painter or the choice of a monochrome red abstract screen print from Rachid Johnson about COVID, BLM and George Floyd, according to the press release. Figurative is one of the hallmark of neo expressionism, in reaction to abstract. The three women selected for the show, Miriam Beerman, Nicole Eisenman and Orit Hofshi meet the neo expressionism criteria, from technique to subject. All the works reflect angst, a few of them are related to German expressionism.

The ambitious goal of the exhibition as stated by Kaywin Feldman, director of the National Gallery of Art is "to invite visitors to consider the striking parallels between the intensity of human emotion and experience conveyed in the work of the German expressionists during a transformational historic period in the early 20th century and current responses to the cultural and political shifts taking place in our world today." The result is a superficial review of German expressionism through prints. The wall texts give little information about the political context or the influence of Die Brücke which is not even mentioned. For decades, the poorly understood movement in France and even America was labelled as "une erreur gothico-teutonique" (a gothico-teutonic mistake). The sweeping statements erode history especially art history and imply that expressionism was invented by German artists. The means of conveying inner emotions in an expressionistic way is independent of time. The wall texts are cursory and offer little information about the artists who might not be well known by some visitors, missing the educational mission of the museum. The exhibition leaves a chilling message: a look at the past does not forebode well for the future.

photographs by the author:

Erich Heckel "Portrait of a Man (Self-Portrait)", 1919

Otto Mueller "Two Bathers", c. 1920

Leonard Baskin "The Hydrogen Man", 1954

Emil Nolde "Dancer", 1913